Com a pandemia da Covid-19, e a respectiva migração de múltiplas experiências e vivências para o plano digital, várias dimensões do nosso quotidiano passaram a ser determinadas pelo online de uma forma ainda mais intensa, praticamente inescapável.

Um dos territórios onde isso aconteceu de maneira mais explícita – com entusiasmo e receio, inventividade e aborrecimento em doses iguais – foi o das artes e fruição cultural. De repente, com tudo de portas fechadas, com artistas e programadores em casa, a cultura passou a estar maioritariamente no mundo virtual, o que simultaneamente trouxe à tona e acelerou um processo já em curso: a transição digital da produção artística e, por arrasto, de um ecossistema financeiro, curatorial, social, afectivo que a sustenta e que está a ser reconfigurado neste outro plano, em moldes ainda pouco consolidados, alguns deles obscuros e armadilhados, mas definitivamente em fase de experimentações e possibilidades várias.

Esta transição não se materializa numa substituição do presencial pelo digital, como vimos e vemos pela continuidade de actividades culturais em espaços físicos – ainda que com uma série de limitações e percalços -, à medida que as restrições sanitárias foram, e vão sendo, aliviadas. Mas sim naquilo que é o grande hot topic, e dilema, do momento: uma realidade híbrida, uma coexistência entre os dois mundos, sobretudo na música, nas artes performativas, nas artes visuais e na arte multimédia, que já andava a ser construída e ensaiada, porém sem a projecção e a abrangência registadas nos últimos tempos. Em Portugal, onde o debate sobre estes tópicos ainda é prematuro, encontramos algumas instituições culturais que já assumiram levar avante esta complementaridade.

O Teatro Municipal do Porto, por exemplo, vai passar a ter dupla existência, no digital e no presencial, depois de uma série de experiências ao longo da última temporada, incluindo uma edição mista do DDD – Festival Dias da Dança.

O gnration, em Braga, lançou um novo ciclo de programação com periodicidade mensal, o Órbita, pensado exclusivamente para o formato online e alimentado por obras encomendadas de raiz onde são estabelecidas pontes com o programa presencial, cruzando música, arte e tecnologia, adianta o director artístico Luís Fernandes. “Estamos numa fase que deu, dá e dará origem a utilizações menos felizes da tecnologia, mas acredito que também abrirá caminho para coisas super interessantes. Estamos a aprender a lidar com o digital como meio de exposição de conteúdos artísticos e como meio de criação.”

“O hibridismo veio para ficar, sem dúvida”, declaram Guilherme Marques e Natália Machiavelli do MITsp – Mostra Internacional de Teatro de São Paulo. A pandemia fez com que a equipa do festival brasileiro concretizasse uma ideia que já andava a germinar nas suas cabeças há vários anos: uma plataforma digital que funcionasse como um tentáculo do evento e onde coubesse o seu acervo, desde espectáculos filmados a cenas de bastidores e entrevistas com criadores, mas também como uma extensão reforçada da vertente pedagógica do projecto, com seminários, aulas abertas, oficinas, olhares críticos. Assim nasceu a MIT+. Depois de uma experiência-piloto no ano passado, transmitindo online os espectáculos que não puderam subir a palco na recta final do festival por causa do raiar da pandemia, esta plataforma foi lançada oficialmente em Março. Continua activa, com acesso gratuito e pondo em prática políticas de acessibilidade como a linguagem gestual e a audiodescrição (políticas essas que se têm tornado mais comuns nas programações online). Para Novembro está previsto uma pequena mostra com espectáculos inéditos brasileiros e uma retrospectiva de peças, também nacionais, das três últimas edições do evento.

Sem ter como objectivo “fazer um festival virtual”, até porque “o teatro no presencial é insubstituível”, Guilherme Marques e Natália Machiavelli querem fazer crescer esta plataforma. “Eu e a Natália estamos conversando sobre a possibilidade de ter um banco de espectáculos – espectáculos históricos, que quase já não circulam – que o público possa ver de forma acessível e que as companhias possam ser remuneradas por isso”, revela Guilherme, criador do festival juntamente com Antonio Araujo. “A plataforma terá de ficar muito mais completa para podermos passar a cobrar uma mensalidade, por exemplo, mas teremos sempre conteúdos gratuitos”, informa Natália, artista multimédia e responsável pela plataforma. “Por outro lado, a ideia é também criar uma ferramenta de busca que seja útil para pesquisadores do teatro e académicos, ao mesmo tempo que o público não especializado consiga navegar por várias temáticas”, acrescenta. “Eu vejo a MIT+ com o mesmo peso em termos de cultura e pedagogia.”

Em relação a estruturas e eventos culturais do circuito institucional, que gozam de estabilidade financeira, é certo que a entrada no digital passou muito pela banal e pouco recompensadora transmissão de espectáculos, gravados ou em live streaming. Contudo, aquilo que alguns conseguiram trazer de minimamente diferenciador foi, por um lado, o tratamento online e a disponibilização ao público dos seus arquivos (a Culturgest criou uma biblioteca virtual através da qual se tem acesso a micro-sites temáticos, vídeos de conferências e espectáculos, áudios, fotografias ou documentação), e, por outro, a aposta redobrada, ou mesmo triplicada, em actividades com um pendor altamente pedagógico e reflexivo que cruzam as artes com a produção e a partilha de pensamento em vários espectros (como aconteceu no Teatro do Bairro Alto).

“Com algumas excepções, as instituições culturais sempre foram conservadoras no que toca à internet. Ou seja, sempre a utilizaram como um órgão de comunicação, uma vitrine, e com a pandemia ela teve de passar a ser a plataforma produtora e apresentadora de conteúdos”, observa o português João Fernandes, director artístico do Instituto Moreira Salles (IMS), que se desdobra em três unidades no Brasil (São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Poço de Caldas). Tem sido um dos bons exemplos de como reperspectivar as actividades de um museu/centro/organização cultural no plano online, a par de entidades como o New Museum (EUA), Centro Cultural São Paulo (Brasil), Kiasma (Finlândia), FACT Liverpool (Inglaterra) ou a plataforma LUX (Inglaterra), pioneira na ponte entre o físico e o digital. “É fundamental, hoje, uma instituição ser produtora de conteúdo cultural e artístico online e não apenas uma transmissora ou retransmissora. Essa é a grande transformação que está a acontecer nas instituições culturais e julgo que não vai parar.” Para o ex-director artístico do Museu de Serralves e ex-subdirector do Reina Sofía, esta transformação terá de ser manobrada sempre numa dinâmica “de enriquecimento recíproco” entre o digital e o presencial – “porque isso cria maiores possibilidades de riqueza de conhecimentos” -, sublinhando que a vida online ao longo deste período “mostrou-nos muita coisa”.

“A pandemia confrontou as instituições com a sua forma de estar, de trabalhar, de agir, e esta quase ignorância e este desdém em relação às culturas online têm de ser do passado.”

Não é por acaso que o debate sobre os museus e as galerias enquanto espaços elitistas, para os mesmos de sempre (sejam estes artistas, curadores e espectadores) tem vindo a ganhar tracção no último ano e meio, em grande medida turbinada por quem esteve e está na dianteira desta discussão: criadores, investigadores e outros dinamizadores da arte digital, agora com maior visibilidade. “A acessibilidade da arte digital fora do cubo branco tem mostrado que há novos públicos a que as galerias, museus e institutos de arte não conseguem chegar nem conectar-se com. Isto é algo que não podem ignorar”, considera Zaiba Jabbar, artista multimédia, curadora independente e fundadora da HERVISIONS, agência curatorial online e offline centrada no cruzamento entre arte, tecnologia e cultura, e orientada para mulheres e pessoas não binárias.

“Enquanto mulher racializada da classe trabalhadora, eu nunca tive a sorte de me poder considerar artista num sentido tradicional. Por isso é que comecei a olhar para as margens, para estas práticas multidisciplinares e antidisciplinares, e quis explorar a arte nos novos media e nas redes sociais”, continua Jabbar. “A mudança em direcção ao digital, intensificada pela pandemia, foi atiçada por artistas digitais que já existiam em comunidades de nicho, a par do apelo a artistas que trabalham em disciplinas mais tradicionais para começarem a explorar este tipo de espaços.” Se, por um lado, há uma maior democratização nestas plataformas, este novo foco de atenção pode adubar terreno para replicar e perpetuar hierarquias e desigualdades do IRL, considera a curadora. E isso mete ao barulho a nova economia criativa que se tem vindo a desenvolver no online, ancorada, em parte, nas promessas da Web3, uma nova era da internet em teoria mais descentralizada e horizontal.

S4RA, artista digital com base em Lisboa, assinala que “o obstáculo do digital em aceder ao circuito mainstream da arte” tem-se devido, em parte, “à dimensão imaterial e à dificuldade em monetizar estas obras, que muitas vezes estão acessíveis online e daí não terem estatuto de propriedade/autenticidade”. Nota que os NFTs vieram “resolver parte deste problema, mas acentuar e perpetuar ainda mais o desnivelamento entre quem capitaliza e os artistas que alimentam a blockchain na esperança do cripto milagre”.

“A dinâmica de mercado é muito semelhante e desmoralizadora na perspectiva de um futuro próximo sustentado num sistema descentralizado. No entanto, parece ser o passaporte para a validação da entrada no mercado da arte porque materializa um suporte que pode finalmente ser comercializado”, aprofunda S4RA. Zaiba Jabbar também partilha da visão de que há vários flancos e possibilidades em confronto. “O mercado dos NFTs ainda é muito dominado pelos bros da tecnologia, mas acredito, ao mesmo tempo, que há uma oportunidade gigante para que os artistas digitais possam monetizar a sua força de trabalho e o valor do digital.” Do lado das instituições culturais mais tradicionais, estas movimentações poderão ser também uma ocasião para pensar o digital não só enquanto espaço de exposição, criação e promoção, mas também como ferramenta de monetização. Estamos, portanto, num momento em que está tudo em aberto. Para o bem e para o mal, entre múltiplos prós e contras.

“Embora se esteja a assistir a uma fetichização em torno dos valores astronómicos de vendas sem precedentes, a espelhar o lado menos bom do mercado IRL, também se potenciou o aparecimento de plataformas geridas por artistas e o desenvolvimento de criptomoedas mais ecológicas”, refere S4RA. “Outros modelos foram adoptados em espaços virtuais como o Cryptovoxels, onde é possível adquirir uma galeria virtual e transaccionar NFTs ou videojogos em que se ganha tokens e se compra assets em criptomoeda. Da necessidade de criar exibições online desenvolveram-se plataformas virtuais, como a New Art City, geridas por artistas de forma a serem o mais inclusivas possível e acessíveis para quem quiser ter o seu próprio espaço navegável online no Mozilla Hubs, VRChat ou AltspaceVR. Deste metaverso, ou processo de replicar a realidade através de meios digitais, ainda há espaço e potencial de expansão em ambos os sentidos.”

Num meio em que o espírito de comunidade é reivindicado e nutrido com especial cuidado, tanto S4RA como Zaiba Jabbar defendem que as pontes entre o digital e o presencial devem ser arquitectadas sem antagonismos, de modo a permitir uma intersecção de várias identidades e backgrounds nas duas dimensões e evitar que se caia numa mera virtualização da cultura. Nesse sentido, S4RA – neste momento a colaborar com uma equipa interdisciplinar numa performance ancorada “num formato híbrido entre o real/material e o virtual em palco”, a estrear num teatro de Lisboa – sublinha que é preciso apostar na “criação de projectos multidisciplinares, ou transmedia, que se estendam ao virtual e dêem espaço a outras vozes que são também outros contextos”. Entre vários exemplos, destaca o videojogo/ arquivo online interactivo Black Trans Archive, de Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley.

Eventos no digital e o dilema da democratização

Dentro do circuito musical, o sector mais afectado pela pandemia, festivais como o Rewire, Unsound, No Ar Coquetel Molotov e CTM (que em 2022 terá um modelo híbrido) montaram edições online em que as conexões entre tecnologia, música e as potencialidades artísticas e comunitárias do digital foram trabalhadas diligentemente. Fizeram-no através de concertos transmedia, performances audiovisuais colaborativas, ambientes 3D, projectos interactivos, workshops, programas de mentoria, clubbing em plataformas virtuais, filmes, videoarte, programas de rádio e conversas que ecoaram as transformações e experiências em curso na indústria musical nesta transição digital. Ao mesmo tempo, abrindo espaço para reflectir e debater em conjunto sobre as implicações sociais, políticas, culturais e psicológicas da pandemia.

“Na primeira edição do Coquetel Molotov.EXE fizemos uma programação que durou 12 dias com oficinas, masterclasses, uma festa surpresa inaugurando a plataforma SpatialChat e um dia de música com quatro ‘palcos’ imersivos pelo Zoom e salas surpresa”, conta a directora Ana Garcia. “Mais de quatro mil pessoas participaram. Foi óptimo receber mensagens de pessoas de todo o Brasil falando como foi incrível a primeira experiência no Coquetel Molotov.”

Sem querer simular “o físico”, mas mantendo “a identidade do festival”, foram criados outros desdobramentos do evento, como a série audiovisual Coquetel Molotov – Etapa Minas Gerais, que deu protagonismo a artistas da cena contemporânea local, e o segundo round do Coquetel Molotov.EXE, em formato revista digital, com performances musicais gravadas, oficinas, textos, trabalhos de fotografia, podcasts ou videoarte de artistas pernambucanos (descobrir em coquetelmolotov.com.br.exe). “Este projecto nasceu de um edital que foi aberto para socorrer a cadeia cultural local”, explica Ana Garcia. “Focamo-nos em obras inéditas e priorizamos novos criadores: muitos deles se lançaram durante a pandemia, não podendo circular pelos palcos locais e também não podendo chamar a atenção de um festival online padrão”, observa. “De certa forma, isto reverbera no princípio de um bom festival de música, que é ser palco para novos nomes.”

Também com o objectivo de estimular os criadores e apoiá-los financeiramente numa fase particularmente dramática – não só devido ao abismo sociopolítico do Brasil agravado pela crise pandémica, mas também por causa do desmonte da cultura levado a cabo pelo governo de Bolsonaro -, o IMS lançou, em Abril do ano passado, o programa Convida, comissionando novas obras para o seu site de 171 artistas e colectivos das periferias das grandes cidades brasileiras e de regiões fora do eixo São Paulo-Rio. Ventura Profana, Leona Vingativa, Grace Passô, Takumã Kuikuro, Ajeum da Diáspora ou o Coletivo Afrobapho foram alguns dos contemplados. “Partindo dos nossos saberes e experiências na instituição, e tendo em conta que o IMS programa e tem acervos nas áreas do cinema, fotografia, iconografia, música, literatura, mais a programação de artes visuais, juntamos todas as áreas, inclusive a educativa, para construir um programa online que fosse um incentivo aos artistas e que se pautasse por critérios de diversidade racial, de género, de orientação sexual e também regional”, contextualiza João Fernandes. “Se nós tivéssemos de nos movimentar para ir ao encontro de todos deles, em tantos lugares, isso teria sido impossível sem o online.”

Por cá, festivais de música como o Boom e o Semibreve ensaiaram, de maneiras distintas, uma presença no digital. No caso do primeiro, a estratégia passou essencialmente por “pegar no lado do Boom associado ao conhecimento e dar ferramentas às pessoas para lidarem com a questão pandémica”, diz Artur Mendes, co-manager do evento. No site do festival é possível encontrar um conjunto de rubricas, entre elas a série de vídeos Boom Toolkit for Covid-19, em que promotores, artistas, terapeutas, cientistas e outros profissionais de diversas valências reflectem sobre temas como a saúde mental na indústria da música (e fora dela), a sustentabilidade e a biodiversidade (marcas identitárias do festival), a natureza e a arte enquanto ferramentas terapêuticas, ou a vigilância digital no capitalismo. Mais uma vez, tal como noutras entidades ligadas à cultura, a produção de pensamento e reflexão revelou-se um dos principais pontos de intervenção neste período.

Houve ainda “uma parte de celebração”, com um streaming realizado a partir da Boomland, “em que o conceito era juntar arte, música, natureza e a arquitectura paisagística do festival, além das suas memórias”, e também a co-criação da plataforma colaborativa internacional de livestream UNITE – Let the Music Unite Us. Contudo, o responsável insiste que, “mais do que dar divertimento às pessoas, o importante é dar-lhes ferramentas numa fase de tanta instabilidade”. Até porque decidiram, desde logo, que não queriam “entrar na nova moda da virtualização da experiência” de um festival. “Não somos contra quem o faz, mas o Boom, pela sua essência, não é de todo replicável num ambiente digital e, ao mesmo tempo, não nos revemos nesta videogamificação dos festivais e da música”, atira Artur Mendes. E a verdade é que há indicadores de que esta “videogamificação” possa vir a tornar-se numa tendência em crescimento – como notou investigadora Cherie Hu no seu Twitter, grandes agentes da indústria musical, como a Sony Music, já estão a investir em mundos 3D e a abrir vagas para profissionais ligados à área do gaming.

Já no Semibreve 2020, festival bracarense voltado para a música electrónica e a arte digital, a aposta foi desenhar um modelo híbrido, mas de uma forma contida, sem tentar “replicar formatos” e ceder ao facilismo do livestreaming. Pela primeira vez, e além das habituais conversas centradas na indústria musical, apostaram “numa linha temática” que valorizou a escuta e uma certa ideia de reclusão. Por um lado, através de encomendas de obras sonoras a artistas como Beatriz Ferreyra, Kara-Lis Coverdale, Ana da Silva ou Jim O’Rourke, tendo em conta as características acústicas e espaciais do Mosteiro de Tibães, onde estas peças puderam ser ouvidas em loop por um número reduzido de público, ao mesmo tempo que ficaram disponíveis no site do festival. Por outro lado, através de filmagens de performances (sem público) de nomes como Klara Lewis, Laurel Halo ou Oliver Coates, que estiveram em residência artística em Mire de Tibães. Os registos das actuações foram exibidos online e no Mosteiro.

Estas performances, nota Luís Fernandes, foram transmitidas em parceria com o Canal 180 e a Fact Magazine, atingindo visualizações “em torno dos 5, 6 mil” por cada vídeo. “Seria impossível chegar a esses números num espectáculo presencial, mas a relação que as pessoas estabelecem com o conteúdo online é totalmente diferente. É muito menos profunda, é mais de consumo rápido. Este ano houve carradas de conteúdos online e isso cria confusão; é muito difícil estar a par de tudo”, observa o programador, também director artístico do gnration. “No fundo é uma falácia, porque a medição em números talvez não reflicta a força da tua proposta artística. E depois há os algoritmos… É uma experiência mediada por muitos factores que estão fora do nosso controle.”

Para Artur Mendes, “os algoritmos são mais potentes do que qualquer conteúdo”. Por isso acredita que o maior alcance geográfico da internet não é, necessariamente, sinónimo de um acesso mais democrático e transversal. “Infelizmente existem as barreiras das grandes corporações tecnológicas, ligadas à mercantilização do acesso à informação.” João Fernandes aprofunda o dilema. “A democracia dentro de uma instituição cultural tem de responder a questões éticas da acessibilidade, que excluem tantas pessoas da vida social e cultural. Isso continua a ser um dos principais problemas de qualquer instituição cultural”, considera. “A grande questão é como é que esta cria os utensílios para ser questionada, interpelada, e para construir uma visão crítica sobre aquilo que faz, e sobre o mundo em que se insere, juntamente com os seus visitantes e utilizadores. E isso a tecnologia não garante por si só: a tecnologia pode ser a expressão dos velhos sistemas de manipulação, de imposição de imagens e de discursos.”

O director artístico do IMS confessa que é “assustador” pensar em como os algoritmos funcionam. “Nós já percebemos que se transmitirmos um espectáculo que tenha um conteúdo patrocinado em plataformas virtuais, o algoritmo trabalha a favor do evento e algo que chegaria a 10 mil pessoas chega a 40 mil. Mas o problema é como se chega a essas 40 mil e para o que é que se chega. A questão não pode ser apenas ter milhões de seguidores; tem de ser aquilo que se faz com as pessoas.” João Fernandes – tal como Ana Garcia do Coquetel Molotov, tal como os responsáveis do MITsp – acredita que a disseminação geográfica ampliada pela internet é extremamente importante num país de dimensões continentais como o Brasil, onde poucos têm condições materiais para se deslocar aos eventos que acontecem nas principais cidades. Porém, Fernandes alerta que as estruturas culturais não se devem “dedicar de uma forma entusiasta ao culto dos algoritmos”, mas sim desempenhar “um papel importante nessa discussão” junto dos públicos, já que estes mecanismos “também reproduzem sistemas de saber e da economia dominantes, bem como as consequentes exclusões determinadas por eles”.

Além das possibilidades supostamente mais participativas que estão a ser desbravadas na Web3, incluindo uma “economia da interdependência” que pode aliar o offline ao online [ver no final a conversa com Mat Dryhurst], contrapor esta ditadura dos algoritmos com “cadeias de cumplicidade, solidariedade e contacto” com artistas, em que estes possam ser também “propulsores” dos seus pares – como sucedeu no programa Convida do IMS, como tem vindo a suceder com a inspiradora mobilização internacional de rádios comunitárias online, entre elas a palestiniana Radio Alhara e libanesa Radio Karantina – é uma “das reflexões e práticas diárias” que devem ser ensaiadas, sugere João Fernandes. E se isso não implica subestimar as redes formadas no digital, também é certo que tem de passar, necessariamente, pelas comunidades presenciais. No caso específico da música, pelo ao vivo.

O presencial é insubstituível

“Tivemos um alcance maior de público com as transmissões das performances, mas claramente foi unânime esta sensação de perda, de saudade do presencial. Por isso decidimos logo no início do ano, sem saber se iria ser possível por causa das regras sanitárias, voltar a fazer um Semibreve físico em Outubro, ainda que com um complemento digital”, afirma Luís Fernandes. Também a equipa do Tremor, na ilha de São Miguel, nos Açores, decidiu ir em frente com a edição deste ano. “Achamos mesmo importante as coisas acontecerem. Mesmo que seja num formato diferente, mesmo que tenhamos de lidar com contingências em termos de booking e de público, mesmo que tenhamos de perder coisas como o clubbing ou a circulação entre vários espaços”, declara Márcio Laranjeira, um dos responsáveis pelo festival.

Em compensação, conceberam um programa expositivo em que “usam a ilha como uma galeria”, com instalações artísticas ligadas à música; desenharam trilhos pedestres acompanhados por composições sonoras site-specific; fortaleceram a aposta em artistas portugueses, o que permitiu “concretizar desejos antigos”, como ter os Clã no line-up, além de com isso sublinharem que “as bandas portuguesas não servem só para abrir cartazes de festivais”. A continuação das residências artísticas com comunidades locais como a Escola de Música de Rabo de Peixe, ondamarela e a Associação de Surdos da Ilha de São Miguel adquiriu, este ano, uma relevância redobrada.

“Várias instituições e associações que realizam um trabalho muito significativo na ilha estiveram quase abandonadas durante a pandemia, de portas fechadas, e o festival serviu também para reactivar essas estruturas com o pouco que podemos fazer”, explica Márcio Laranjeira. Não é por acaso que o Tremor se autodenomina como “um evento de pessoas, caras e comunidades”. “Antes da pandemia falava-se muito, de forma depreciativa, da parte social da música, e acho que hoje percebemos que esse factor é muito importante, mesmo nos festivais em que a curadoria é a bandeira. Não é só ver concertos: é estar com pessoas, conhecer pessoas, e isso é essencial para o ser humano.”

A preservação, criação e renovação de comunidades presenciais também faz parte do ADN, do metabolismo das salas independentes de programação de música ao vivo: as chamadas grassroots music venues, que passaram o último ano e meio a tentar sobreviver sem políticas de apoio realmente estruturadas e estruturantes. Mesmo quem pôde abrir portas para funcionar a meio-gás, na maior parte dos casos sem poder levar a cabo a sua actividade programática habitual, sentiu que continuou a servir de âncora para os seus públicos.

“A comunidade artística que sempre nos rodeou continuou a fazê-lo, mas de outra forma. Foi mais uma salvaguarda de afectos mútuos, de conversas, de desabafos, de partilha de perspectivas”, conta Alexandra Vidal, co-fundadora e co-programadora das Damas, em Lisboa. “Fomos mais um consultório de psicologia do que uma sala de concertos no último ano e meio. De certa maneira, ainda bem que assim foi.” No Village Underground (VU), também na capital, a pandemia acabou por fazer com que a programação ganhasse um cunho mais autoral, em parte “virada para uma comunidade que gosta de música nova, por descobrir”, refere Mariana Duarte Silva. “Nesta nova fase” dão palco, de terça a domingo, “a talentos das mais variadas famílias musicais”, e isso, assinala a responsável, “veio mesmo para ficar”. Paralelamente, o VU pôs em marcha a Skoola, que tem como missão cardeal estimular a criação de comunidades através do ensino não formal de música.

Para Pedro Azevedo, programador do Musicbox Lisboa, da Casa do Capitão e do festival MIL, a partir de agora as grassroots music venues vão ter de começar “a pensar seriamente” em como “pôr os putos a fazer música” e a “torná-la numa profissão mais viável” no futuro. “Claro que isso tem de ser reforçado ao nível mais institucional, mas também vai ter de passar por nós, programadores destas salas”, analisa. “O meu trabalho vai ser apostar no circuito local, incentivá-lo e desafiá-lo. A questão das residências artísticas é fulcral: ou seja, pôr pessoas a trabalhar umas com as outras.” Este diagnóstico, nota Pedro, surge da constatação de que a pandemia provocou “danos profundos” no tecido da criação musical independente, inclusive na estabilidade emocional dos músicos e na vontade em continuar a fazer o que fazem.

“Os danos são muitos, sejam eles na forma de ausência de oportunidades para a comunidade artística, na diluição das comunidades em espaços que programavam, mas sem ter grandes capacidades de profissionalização, ou toda a música que devia ter sido apresentada e não foi”, reforça Alexandra Vidal. “Perderam-se muitos primeiros concertos, perdeu-se muita promoção com pés e cabeça.

No entanto, o futuro parece vir a beneficiar de estruturas que se foram criando entre os pingos da chuva da pandemia.” O programador do Musicbox acrescenta outro ponto. “As próximas gerações não vão ter confiança para seguir uma carreira musical. E se antes já não era bem visto pela família, agora ficou tudo ainda mais exposto com a pandemia. Os músicos tiveram ou zero apoios ou apoios muito insuficientes.”

Pedro Azevedo diz ainda que, no caso da música ao vivo, em particular nestes circuitos locais, é preciso olhar com cautela para as implicações do digital. Se nas artes visuais e intermédia, e em parte nas artes performativas, a discussão parece mais polissémica, neste sector específico a desconfiança sobressai. “Há toda uma nova forma de os artistas trabalharem conteúdos, de se mostrarem, de interagir com os fãs e até de conseguir a atenção das majors, mas isso vai desaguar onde? Ou devia desaguar onde? Num palco. Em Portugal tens uma nova geração de músicos super talentosos, com 50 mil ou mais seguidores no Instagram, que não tocam ou quase não tocam ao vivo e ficam por trás destas plataformas. As bolhas assim ficam cada vez mais fechadas: as dos artistas, as dos públicos, as dos programadores.” Pedro Azevedo admite que pode estar a ser “um velho do Restelo”, mas não consegue ver que outro formato possa ser melhor “do que um palco”.

“A transição digital traz muita coisa boa, mas, nesta área, temos mesmo de pensar em como não dar cabo daquilo que resta do sector da música ao vivo.” Terminemos, talvez de forma enviesada, com as palavras de Mat Dryhurst, artista, investigador e um declarado entusiasta dos novos caminhos da tecnologia, que não é, com certeza, um velho do Restelo.

“A música é, fundamentalmente, sobre congregação. As pessoas numa sala são aquilo que interessa”. Diz-nos, sem rodeios: “A experiência musical ao vivo é o pináculo para mim. É a dimensão da música que é a inveja de todas as outras formas de arte, e não admira que a economia da música ao vivo seja o principal sistema de apoio para os músicos mais interessantes que conheço. Precedeu a indústria discográfica e sobreviverá a tudo aquilo que pudermos imaginar. Para ser sincero, é um dos principais motivos pelos quais faço música, e sem a promessa de haver concertos acho que perderia o interesse.”

Skoola: Uma academia de música informal aberta à comunidade

3 perguntas a Mariana Duarte Silva, directora do Village Underground (VU) e ideóloga da Skoola

O que a música e a sua aprendizagem em grupo fazem é um despertar para a criatividade e para o pensamento crítico, para imaginar outros mundos, aproximar pessoas, aumentar a auto-estima e o sentido de pertença. Por isso, a forma como ensinamos música – o seu lado mais urbano e contemporâneo, aquela que os jovens ouvem – é estruturada em três eixos. Produção musical, criação/ composição e performance, através de um desenho curricular que alia os princípios básicos dos instrumentos às novas possibilidades de fazer música com tecnologia. Cria-se uma comunidade onde todos contribuem para o desenvolvimento de cada um.

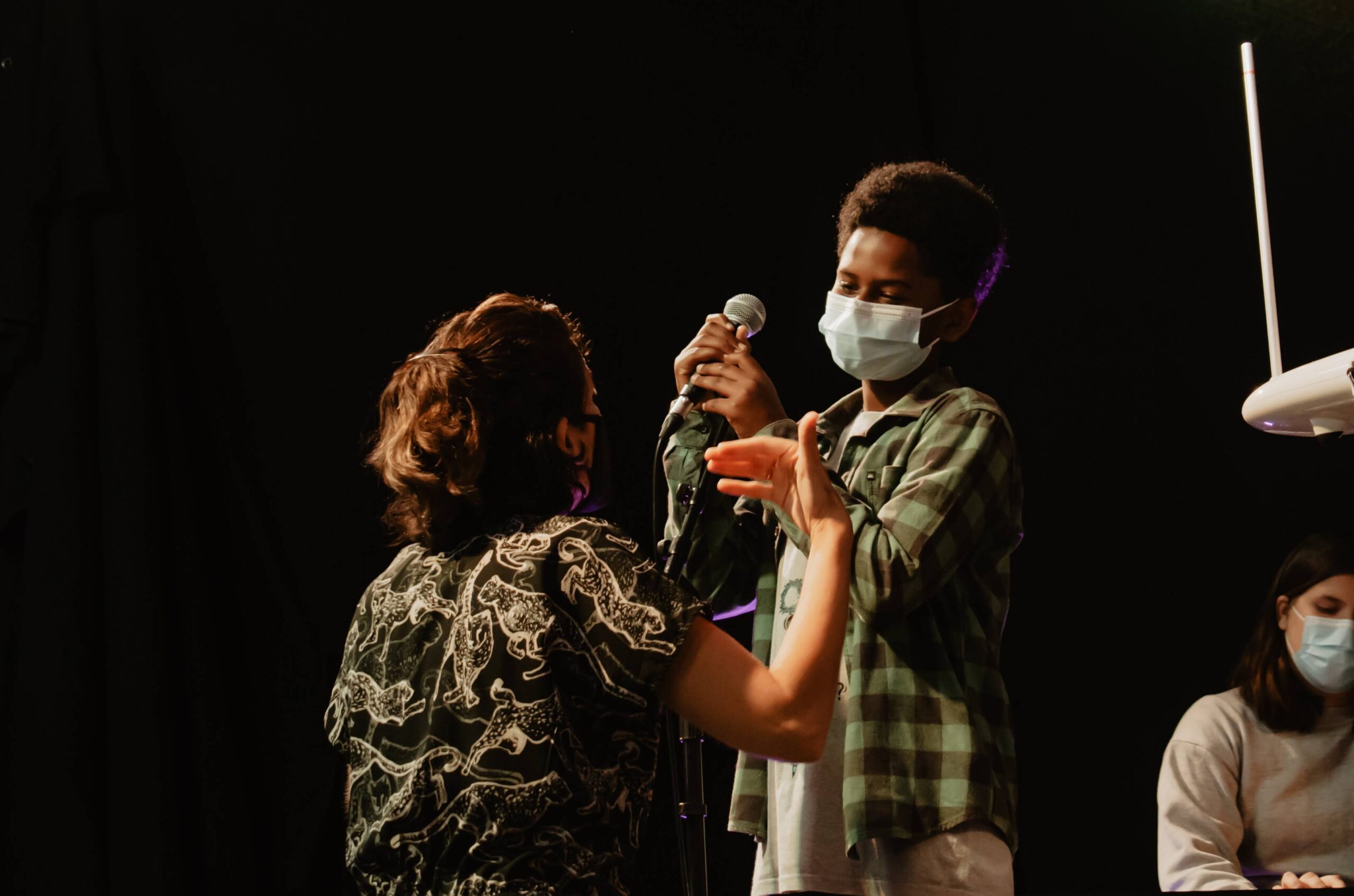

A Skoola é uma academia aberta a jovens de todos os contextos sociais. Temos residentes em bairros como Chelas, Quinta do Loureiro e Liberdade, outros que vivem em casas da Santa Casa da Misericórdia, outros com problemas cognitivos de escolas públicas (todos estes não pagam, são bolseiros) e miúdos e miúdas cuja situação financeira familiar permite pagar a Skoola. Vê-se uma simbiose entre todos quando estão a criar música, bem como nos intervalos: jogam basquete, dançam, desenham, conversam, além de terem grupos no WhatsApp. Entre as muitas histórias que nos revelaram talentos, amizades, artistas e outros possíveis futuros, há a do Ricardo, um jovem de 14 anos da Guiné que vive em Portugal ao abrigo de um protocolo de saúde, porque está a tratar de um problema no olho que o está a cegar. Ele chegou à Skoola com a cara tapada pelo seu hoodie e sem comunicar, mas depois de perceber que podia tocar piano, cantar, escrever letras e ainda aprender a subir a um palco e a mexer numa mixer de DJ, acabou por querer fazer não só a aula com o grupo da sua idade mas também as outras sessões. Agora, o Ricardo liga ao Pedro Coquenão e ao Karlon Krioulo [da equipa de facilitadores do projecto] e vai fazer música com eles para o nosso estúdio.

Com o que disse anteriormente acabo por responder a essa questão. Falámos com directores, psicólogos e assistentes sociais de escolas públicas, cujos jovens frequentaram a Skoola, e todos eles referem a urgência de se implementar este tipo de projectos nas escolas de uma forma regular e construtiva. Posso adiantar que a Escola Básica Marquesa de Alorna, depois de ter assistido ao nosso curso de Verão onde participaram três dos seus alunos, pediu-nos um orçamento para estarmos semanalmente na escola com a Skoola durante o próximo ano lectivo.

Interdependendência vs Independendência

Mat Dryhurst, músico, artista multimédia e um dos pensadores mais desafiantes da indústria musical, não tem dúvidas de que o ecossistema da música como o conhecemos está a ser “destruído a cada ano que passa” e a ser “substituído por plataformas ahistóricas e algorítmicas”. Não é possível voltar atrás, diz, mas é preciso accionar contra-narrativas e outros modos de fazer que tornem este ecossistema mais sustentável e ético, equitativo e inventivo face às novas circunstâncias.

“As pessoas precisam de fazer qualquer coisa, seja o que for. Serem menos avessas ao risco”, declara. A música independente – “o que quer que isso signifique agora” – é “um modelo pronto-a-usar totalmente confortável”. Um ideal domesticado e distorcido com sérias implicações na economia criativa, nas condições laborais dos artistas, na criação de comunidades realmente sólidas.

“O problema com a fetichização da ideia de independência, como vemos na economia das plataformas, é que quando retiras os mecanismos de suporte através da redução de custos acabas por ter resultados bastante insignificantes”, considera. “O sonho da música independente era este mito da soberania absoluta, do ‘ninguém me pode dizer o que fazer’. Em muitos aspectos, a independência conduziu a um isolamento. Ao sentimento de que ninguém está lá para ti, de que tens de fazer escolhas seguras, de que estás em competição com toda a gente e que tens de agir consoante esse impulso, o que não é a atitude mais saudável para fazer boa arte ou desafiar alguma coisa.”

Por isso é que Mat Dryhurst tem sido um pertinaz defensor e promotor do conceito de interdependência, incentivando as possibilidades de uma nova economia criativa descentralizada (ouvir o podcast Interdependence, que partilha com a artista e compositora Holly Herndon). “Tudo o que é especial e ambicioso tem de envolver um grupo alargado de pessoas que precisam de ser respeitadas e remuneradas de modo a que toda a operação funcione”, diz-nos, aludindo à lógica de cooperativismo que sustenta projectos como a plataforma de streaming comunitária Resonate, na qual está envolvido (vale a pena seguir outras iniciativas como a herstoryDAO, Friends with Benefits ou Mycelia).

“Acredito que a interdependência representa a afirmação do valor [económico] e da importância da cultura ao construir novas estruturas e protocolos”, assinala. “Há quem já o esteja a fazer em alguns cantos. Sou bastante fã de UK grime e drill, e mesmo com as condicionantes do YouTube, fico impressionado ao ver como diferentes artistas, produtores e influencers estão todos a conspirar para amplificar o que cada um faz.”

Dryhurst diz-se particularmente interessado nas novas ferramentas que podem ser utilizadas para tornar este tipo de movimentações culturais, e os circuitos musicais, “mais interdependentes financeiramente”. Mas como fazê-lo com as grandes corporações sempre à espreita para capitalizar estas subculturas? O artista e investigador argumenta que as alternativas podem estar na Web3. “Estas culturas abraçam a capitalização porque precisam de ter acesso a dinheiro, e a Web2 tem feito um péssimo trabalho nesse sentido. É por isso que na última década tem sido normalizado que os artistas façam parcerias com marcas, porque a maioria das pessoas já não paga directamente pela cultura e os artistas precisam de comer.”

“Há muitas abordagens possíveis na Web3, mas uma das oportunidades mais cativantes é deter a propriedade dos projectos de forma comunitária”, acrescenta – e isso é algo que ele e Holly Herndon estão a experimentar através da ferramenta Holly+, com base numa tecnologia de governação participativa intitulada DAO – Decentralized Autonomous Organization. Apesar do entusiasmo, Mat Dryhurst admite que a Web3 não é imune a monopólios, nem é “uma espécie de utopia equitativa e horizontal”, nem vai acabar com o capitalismo. Contudo, defende que nela existem “mais meios para prevenir que a monopolização aconteça de uma maneira generalizada” e permanente. E que “será melhor”.

“Uma das questões centrais que precisamos de abraçar para tornar as coisas melhores é quebrar com a centralização de qualquer mercado de arte ou música”, afirma. “A música está fortemente concentrada nas plataformas de streaming. A minha esperança é que com a Web3 vejamos centenas de mini-economias distintas que sirvam as comunidades.” Também por isso, sublinha, é preciso haver mais pedagogia sobre a Web3, que é ainda pouco compreensível para muita gente – inclusive para que os artistas possam entender como tirar partido destas novas ferramentas.

Given the COVID-19 pandemic and the resultant migration of various experiences and events to the digital realm, numerous aspects of our daily lives suddenly became more intensely – practically unavoidably – determined by the internet. One of the areas in which this was most explicit – with enthusiasm and reluctance, inventiveness and boredom in equal measures – was that of the arts and the enjoyment of culture. Suddenly, with all doors closed, artists and programmers at home, culture moved almost entirely to the virtual realm, which simultaneously brought to the fore and accelerated a process that was already under way: the digital transition of artistic production, dragging behind it its own sustaining financial, curatorial, social and emotional ecosystem, which is also being reconfigured for this new digital stage in as-of-yet fragile moulds, some obscure and full of traps, but definitively in the experimentation phase of multiple possibilities. This transition does not constitute a digital substitution of the in-person experience, as we have seen and continue to see in the continuation of live cultural activities – although still with a set of limitations and obstacles – as health restrictions are lifted. Rather, it is the great hot topic, and dilemma, of the moment: a hybrid reality, a coexistence between two worlds, above all in music, performing arts, visual arts and multimedia art, which was already under construction and being tested, yet without the reach and scope recorded in recent times. In Portugal, where discussion of such topics is still young, we find some cultural institutions that have already taken it upon themselves to move forward with this complementarity. Teatro Municipal do Porto, for example, is going to lead a double existence, both digital and in-person, following a series of experiences over the past season, including a hybrid edition of DDD – Festival Dias da Dança.

gnration, in Braga, has launched a new monthly programming cycle, Órbita, designed exclusively for an online format and fed by works commissioned from scratch, building bridges with the live programme, spanning music, art and technology, says the artistic director, Luís Fernandes. “We’re in a phase that has given rise to, continues to and will still give rise to less fortunate uses of technology, but I believe it will also pave the way for super interesting things. We’re learning to handle digital as both a means of displaying artistic content and a means of creation.”

“Hybridism is here to stay, no doubt about it”, states Guilherme Marques and Natália Machiavelli from MITsp – São Paulo International Theatre Festival. The pandemic led the Brazilian festival team to foment an idea they’d been mulling over for a few years: a digital platform that works as a component of the event and where its own archive is kept, from filmed performances to behind-the-scenes shots and interviews with creators, but also as a reinforced extension of the project’s pedagogical side, with seminars, open classes, workshops and critical perspectives. Thus MIT+ was born. Following last year’s trial run, broadcasting shows online that couldn’t be staged during the final stretch of the festival because of the emerging pandemic, this platform was officially launched in March. It remains active and free to access, employing accessibility policies such as sign language and audio description (policies that have become more common in online programming). For November, there’s a small festival lined up with new Brazilian shows and a look back at national pieces from the last three editions of the event.

Without wishing to “create a virtual festival”, because “live theatre is irreplaceable”, Guilherme Marques and Natália Machiavelli want to see this platform grow. “Natália and I are in conversation about the possibility of having a show bank – past shows, which are almost out of circulation – that the public can access easily and companies can receive compensation for it”, reveals Guilherme, creator of the festival along with Antonio Araujo. “The platform would have to be much more complete to be able to charge a monthly fee, for example, but we’ll always have free content”, states Natália, multimedia artist in charge of the platform. “On the flipside, there’s also the idea of creating a search tool that would be useful for theatre research and academics, while the general public could browse by topic”, she adds. “I consider MIT+ to be as significant in terms of culture and pedagogy.”

With regard to cultural structures and events of an institutional circuit, which enjoy financial stability, their entry into the digital world manifested as the mundane and unrewarding broadcasting of recorded or live streamed shows. And yet, what some managed to bring with notable difference was, on the one hand, online treatment and the availability of their archives to the public (Culturgest created a virtual library for accessing thematic micro-sites, videoconferences and shows, audio files, photographs and documents), and, on the other hand, double or even triple the commitment to activities of a highly pedagogical and reflexive inclination, which combine the arts with production and shared thought across various spectrums (as was the case for the Teatro do Bairro Alto).

“With a few exceptions, cultural institutions have always been conservative regarding the internet. That is to say, they’ve always used it as a means of communication, a window, but the pandemic meant that it had to become the platform for producing and presenting content”, observes Portuguese João Fernandes, artistic director of the Instituto Moreira Salles (IMS), which has three units in Brazil (São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Poço de Caldas). It has provided one of the good examples of how to refocus a museum’s/cultural centre’s activities for moving online, on a par with entities such as the New Museum (USA), Centro Cultural São Paulo (Brazil), Kiasma (Finland), FACT Liverpool (England) and the LUX platform (England), a pioneering bridge between the physical and digital realms. “These days it’s fundamental for an institution to produce online cultural and artistic content and not simply broadcast or retransmit it. That’s the big transformation taking place in cultural institutions, and I don’t think it will end.” For the former artistic director of the Serralves Museum and deputy director of Reina Sofía, this transformation will have to be negotiated always with a “reciprocally enriching” dynamic between digital and in-person – “because this will bring about greater possibilities for enriching knowledge” – highlighting that the online way of life over this period “has shown us a great deal”.

“The pandemic confronted institutions’ way of being, working, behaving, and this almost ignorance and disdain for online cultures must belong to the past.”

It is not by chance that the debate on museums and galleries as elitist spaces, always for the same people (whether artists, curators or spectators), has gained traction over the past year and a half, spearheaded in large part by those who were and are at the forefront of the conversation: creators, researchers and other digital art enthusiasts, now with greater visibility. “The accessibility of digital art outside the white cube has highlighted that there are new audiences whom galleries, museums and art institutes are not reaching or connecting with. This is something they can’t ignore”, considers Zaiba Jabbar, moving image artist, independent curator and founder of HERVISIONS, a curatorial agency both online and offline that focuses on the crossover between art, technology and culture, aimed at women and non-binary people.

“As a working class woman of colour I didn’t feel lucky to ever consider myself an artist in a traditional sense. That’s why I started looking at the margins, to these multidisciplinary and anti-disciplinary practices, wanting to explore new media art or art on social media”, Jabbar continues. “The shift towards digital, accelerated due to the pandemic, really has been ignited by the artists that were existing in the niche community, coupled with a new awareness to artists working in more traditional disciplines that they should be exploring this type of space. ”If, on the one hand, these platforms are more democratised, this new focus could lay the groundwork for replicating and perpetuating IRL hierarchies and inequalities, the curator proposes. And that sets in motion the new creative economy that has been brewing online, anchored in part to the promises of Web3, a new era of the internet, in theory more decentralised and horizontal.

S4RA, a Lisbon-based digital artist, points out that “the main obstacle for digital in reaching the mainstream art world” has in part been “its immaterial dimension and the difficulty in monetising these works, which are often available online and therefore have no ownership/authenticity statute.” S4RA notes that the NFTs came “partly to solve that problem, but accentuate and perpetuate even further the imbalance between those who capitalise on and the artists that feed blockchain in the hope of a crypto-miracle”.

“The market dynamic is very similar and demotivating from the perspective of a near future sustained within a decentralised system. However, it seems to be the passport to validating art’s entry into the market, because it materialises support that might eventually be commercialised”, S4RA continues. Zaiba Jabbar also shares the view that there are various aspects and possibilities to be confronted. “The market of NFTs is still dominated by tech bros, but I believe there’s a huge opportunity for digital artists to monetise on the labour and the value of digital.” As for more traditional cultural institutions, these movements might also be a chance to view digital as not just a space for displaying, creating and promoting, but also as a monetisation tool. We are at a point where everything’s on the table. For better or worse, among the many pros and cons.

“Although witnessing a fetishization around the unprecedented, astronomical sale figures, which reflect the less positive side of the IRL market, we also have the appearance of platforms managed by artists and the development of more ecological cryptocurrency”, mentions S4RA. “Other models have been adopted in virtual spaces such as Cryptovoxels, where you can acquire a virtual gallery and trade NFTs or video games in which you win tokens and buy assets in cryptocurrency. Out of the need to create online exhibitions, virtual platforms have been developed, such as New Art City, managed by artists in order to be as inclusive as possible and accessible to anyone who wants to have their own navigable online space on Mozilla Hubs, VRChat or AltspaceVR. With this metaverse, or process of replicating reality via digital means, there is still space and possibility for expansion in both senses.”

In an environment where community spirit is claimed and nourished with special care, both S4RA and Zaiba Jabbar argue that bridges must be built between digital and in-person without antagonising, to enable the intersection of various identities and backgrounds in both dimensions and avoid falling into the mere virtualisation of culture. In this vein, S4RA – currently collaborating with an interdisciplinary team on a performance anchored “in a hybrid format between the real/material and the virtual on stage”, to be premiered at a theatre in Lisbon – emphasises the need to invest in the “creation of multidisciplinary or transmedia projects, which extend to the virtual and create space for other voices that are also other contexts”. Among various other examples, S4RA highlights the interactive video game/online archive Black Trans Archive, by Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley.

Events in the digital dimension and the dilemma of democratisation

Within the music world, the cultural sector most affected by the pandemic, festivals such as Rewire, Unsound, No Ar Coquetel Molotov and CTM (which in 2022 will take a hybrid form) put together online editions in which the interconnections between technology, music and the artistic and community potential of going digital were diligently elaborated. They did this via transmedia concerts, collaborative audio-visual performances, 3D atmospheres, interactive projects, workshops, mentoring programmes, virtual clubbing, films, video art, radio programmes and conversations that echoed the transformations and experiences taking place in the music industry during this digital transition. At the same time, opening up space for joint reflection and debate on the social, political, cultural and psychological implications of the pandemic.

“In the first edition of Coquetel Molotov.EXE, we created a 12-day programme with workshops, masterclasses, a surprise launch party for the platform SpatialChat, and a day of music with four immersive ‘stages’ via Zoom and surprise rooms”, recounts director Ana Garcia. “Over four thousand people participated. It was brilliant receiving messages from people all over Brazil talking about how incredible their first experience of Coquetel Molotov was.”

Without intending to simulate “the physical”, but maintaining “the festival’s identity”, other offshoots of the event were created, such as the audio-visual series Coquetel Molotov – Etapa Minas Gerais, led by artists from the local contemporary scene, and the second round of Coquetel Molotov.EXE, in the form of a digital magazine, with recorded musical performances, workshops, texts, photography, podcasts and video art by Pernambucan artists (discover more at coquetelmolotov.com.br/exe). “This project arose from a call for proposals that was opened to help the local cultural chain”, explains Ana Garcia. “We focus on unedited works and give priority to new creators: many of them were launched during the pandemic, so were unable to do the rounds on local stages, nor attract the attention of a standard online festival”, she observes. “In some way, this reflects the beginning of a good music festival; a stage for new names.”

Also with the objective of stimulating creators and supporting them financially during these particularly trying times – not just because of Brazil’s socio-political gulf, worsened by the pandemic, but also the cultural dismantling brought to a head by Bolsonaro’s government – the IMS launched the Convida programme in April last year, commissioning new works for its site from 171 artists and collectives from the outskirts of large Brazilian cities and from regions outside the São Paulo-Rio highway. Ventura Profana, Leona Vingativa, Grace Passô, Takumã Kuikuro, Ajeum da Diáspora and Coletivo Afrobapho were some of those considered. “Starting from our knowledge and experiences within the institution, and taking into account that the IMS creates programmes and collections in the areas of cinema, photography, iconography, music, literature, plus the programming of visual arts, we collected all those areas, including education, to put together an online programme that incentivised artists and that was guided by diversity criteria in race, gender, sexual orientation and region”, explains João Fernandes. “If we’d had to travel to find all of them, in so many places, that would’ve been impossible offline”.

As for here, music festivals such as Boom and Semibreve tested their digital presence in distinct ways. The former’s strategy was essentially “to pick up on the side of Boom associated with knowledge and to provide tools for people to deal with the issue of the pandemic”, says Artur Mendes, co-manager of the event. You can find a set of headings on the website, among which is the video series Boom Toolkit for COVID-19, where promoters, artists, therapists, scientists and various other professionals reflect on topics such as mental health in the music industry (and beyond), sustainability and biodiversity (identifying features of the festival), nature and art as therapeutic tools, and surveillance capitalism. Once more, as with other culture-related entities, thought production and reflection proved to be one of the key points of intervention during this period.

There was also “a celebratory part”, with a streaming made from Boomland, “in which the idea was to join art, music, nature and the festival landscape, along with its memories”, and also the co-creation of an international collaborative livestreaming platform called UNITE – Let the Music Unite Us. However, Artur Mendes emphasises that, “more than giving people a fun time, what matters is providing them with these tools during a period of such instability”. They also decided right from the start that they didn’t want to “enter into the new trend of virtualising the experience” of a festival. “We’ve nothing against those who do it, but Boom, in essence, cannot be replicated in a digital environment and, at the same time, we don’t identify with this videogamification festivals and music”, Mendes continues. And the truth is that there are indicators that this “videogamification” might find itself in a growing trend – as researcher Cherie Hu noted on her Twitter page, big agents in the music industry, such as Sony Music, are already investing in 3D worlds and creating job opportunities connected to gaming.

As for Semibreve 2020, a festival in Braga based around electronic music and digital art, the test was drawing up a hybrid model, but in a contained way, without trying to “replicate formats” and giving in to the ease of livestreaming. For the first time, and besides the usual conversations focused on the music industry, they bet on “one thematic line” that valued listening and some idea of isolation. On one hand, they commissioned sound pieces from artists such as Beatriz Ferreyra, Kara-Lis Coverdale, Ana da Silva and Jim O’Rourke, taking into account the spatial and acoustic features of Monastery of Tibães, where these pieces could be heard on a loop by a select public audience, at the same time that they were available on the festival website. On the other hand, they filmed performances (without an audience) from names such as Klara Lewis, Laurel Halo and Oliver Coates, who were resident artists in Mire de Tibães. The recorded performances were displayed online and in the monastery.

These performances, notes Luís Fernandes, were streamed in partnership with Canal 180 and Fact Magazine, reaching “around 5 or 6 thousand” views per video. “It would be impossible to achieve these numbers with an in-person show, but the relationship people establish with online content is completely different. It’s far less profound, more immediate consumption. This year there were truckloads of online content, and that creates confusion; it’s hard to keep up with everything”, observes the programmer, who is also the artistic director of gnration. “Deep down it’s a fallacy, because measuring in terms of numbers might not reflect the impact of your artistic offering. And then there are the algorithms… it’s an experience mediated by many factors that are beyond our control.”

For Artur Mendes, “the algorithms are more powerful than any content”. That’s why he believes that the greater geographical reach of the internet is not necessarily synonymous with more democratic and transversal access. “Unfortunately, there are the barriers of tech giants, linked with commercialising access to information”. João Fernandes expands on the dilemma. “Democracy within a cultural institution has to answer ethical questions of accessibility, which exclude so many people from the social, cultural life. That continues to be one of the main problems for any cultural institution”, he adds. “The big question is how this creates the instruments necessary for questioning, challenging, and building a critical view of what we do, and of the surrounding world, along with its visitors and users. And technology alone cannot guarantee that: technology can be the expression of old processing systems, of imposing images and discourses.”

The artistic director of the IMS admits that it’s “scary” to think about how algorithms work. We already understand that, if we broadcast a show that contains sponsored content on virtual platforms, the algorithm works in favour of the event and something that would reach 10 thousand people reaches 40 thousand. But the issue is how and why it reaches those 40 thousand people. It can’t simply be a matter of having millions of followers; it must be what we do with those people.” João Fernandes – just like Ana Garcia from Coquetel Molotov and those in charge of MITsp – believes that the geographical dissemination amplified by the internet is extremely important in a country the size of Brazil, where few have the material comforts for travelling to events in the main cities. However, Fernandes warns that cultural structures mustn’t “devote themselves too keenly to the cult of algorithms”, rather they should play “an important role in this conversation”, along with audiences, since these mechanisms “also reproduce dominant knowledge and economic systems, as well as the exclusions determined by them.”

Besides the supposedly more participatory possibilities that are being explored on Web3, including an “economy of interdependence” that could unite the offline with the online, and counter this dictatorship of algorithms with “chains of complicity, solidarity and contact” with artists, in which they can also be “driving forces” behind their partners – as happened in the IMS programme Convida, and as has come to pass with the inspiring international mobilisation of online community radios, among them Radio Alhara from Palestine and Radio Karantina from Lebanon – is one of the “daily reflections and practices” that should be tested, suggests João Fernandes. And while this doesn’t necessarily imply underestimating digitally formed networks, for sure one has to pass through in-person communities. As for the specific case of music, this is live performance.

In-person is irreplaceable

“We had greater public reach with performance broadcasts, but there was clearly a unanimous sense of loss, of longing to be present. That’s why we decided right from the start of the year, without knowing whether it would be possible because of health restrictions, to return to Semibreve in person in October, even if with a digital supplement”, affirms Luís Fernandes. The Tremor team, on the island of São Miguel in the Azores, also decided to go ahead with a production this year. “We consider it truly important that these things should happen. Even in a different format, even if we have to have a contingency plan for bookings and audiences, even if we have to cut things like clubbing or moving between different stages”, states Márcio Laranjeira, one of the people in charge of the festival.

To compensate, they came up with an expository programme in which they “use the island as a gallery”, with art installations connected to music; they drew up walking trails accompanied by site-specific sound pieces; and they strengthened the investment in Portuguese artists, which allowed them to “consolidate long-standing wishes”, such as having Clã in the line-up, highlighting that “Portuguese bands are not just festival warm-up acts”. The continuation of artist residences with local communities, such as the Rabo de Peixe Music School, ondamarela, and the São Miguel Deaf Association, has taken on special importance this year.

“Various institutions and associations that do highly meaningful work on the island were almost abandoned, with their doors closed during the pandemic, and the festival also served to revive these structures with what little we could do”, explains Márcio Laranjeira. It is not by chance that Tremor describes itself as “an event of people, faces and communities”. “Before the pandemic, there was much disparaging talk of the social side of music, and I think we now understand the importance of that aspect, even in festivals where curatorship is the main appeal. It’s not just seeing concerts: it’s being with people, getting to know people, and that’s essential to human beings”.

The preservation, creation and renewal of in-person communities is also part of the DNA, the metabolism, of independent grassroots music venues, which have spent the past year and a half trying to survive without any truly structured or structural support policies. Even those who were able to open their doors to be semi-functional, in most cases without being able to offer their usual programming, felt that they continued to serve as an anchor for their audiences.

“The artistic community that has always surrounded us has continued to do so, just in another way. It was more a safeguard for mutual affection, conversation, letting off steam, and sharing perspectives”, tells Alexandra Vidal, co-founder and co-programmer of Damas, in Lisbon. “We’ve been more of a psychologist office than a live music venue over the past year and a half. In some ways, it’s just as well.” At Village Underground (VU), also in the capital, the pandemic ended up giving their programming a more authorial mark, in part “aimed at a community that likes having new music to discover”, states Mariana Duarte Silva. “In this new phase” they provide the stage, from Tuesday to Sunday, “for talent from an array of musical genres”, and that, he points out, “is here to stay”. Likewise, VU set Skoola in motion, whose primary mission is to stimulate the creation of communities via informal music education.

For Pedro Azevedo, Musicbox Lisbon, Casa do Capitão and the MIL festival booker, as of now grassroots music venues will have to start “thinking seriously” about how to “get the kids making music” and “make it a more viable profession” in the future. “Of course that has to be reinforced at a more institutional level, but it will also have to come via us, the bookers of these spaces”, he observes. “My work will be to invest in the local music scene, to incentivise it and challenge it. Artist residencies are crucial: in other words, putting people to work one with another.” This diagnosis, notes Pedro, arises from his observation that the pandemic “damaged deeply” the fabric of independent musical creation, including musicians’ emotional stability and their desire to keep doing what they do.

“The damage is extensive, whether in the lack of opportunities for artistic community, the dilution of communities in spaces where they were programmed but without much development of their professional skills, or all the music that should have been performed but wasn’t”, adds Alexandra Vidal, reinforcing the point. “We missed out on so many first concerts, we missed out on so much well done promotion.

And yet, it seems the future will benefit from structures that were created between the raindrops of the pandemic.” The Musicbox booker continues: “Future generations won’t have the confidence to follow a career in music. And if it wasn’t held in high esteem by the family before, now it’s been truly laid bare by the pandemic. Musicians have had zero or drastically insufficient support.”

Pedro Azevedo also says that, in the case of live music, particularly in these local circuits, there is a need to consider the implications of going digital with caution. While in the visual arts and intermedia, and in part in performing arts, the discussion seems more varied, in this particular sector, mistrust stands out. “There’s a whole new way for artists to work on content, to showcase themselves, to interact with fans and even to attract the attention of major record labels, but where is it leading? Where should it lead? To the stage. In Portugal, you have a new generation of extremely talented musicians, who have 50 thousand plus followers on Instagram, but who never or almost never play live, and stay behind these platforms. Thus the bubbles are ever more closed: those of artists, those of audiences, and those of bookers.” Pedro Azevedo admits that he might be “an old man from Restelo” (a Portuguese expression referring to people who resist change), but he can’t envisage anything better than a stage.

“The digital transition brings with it many good things, but, in this area, we really have to think about how not to ruin what’s left of the live music sector.” Let’s finish, perhaps with a little bias, with the words of Mat Dryhurst, artist, researcher and self-declared enthusiast of new technology, who is certainly not an old man from Restelo.

“Music is fundamentally about congregation. The people in the room are what matters.” He tells us, with no reservations: “The live experience of music is the pinnacle for me. It is the one dimension to music that is the envy of all other art forms, and it is no wonder that the live music economy is the main support system for the most interesting musicians I know. It preceded the recorded music industry and it will outlive whatever we are thinking about. To be honest, it’s one of the main reasons I make music, and without the promise of shows I think I would lose interest.”

Skoola: an informal music academy open to the community

3 questions for Mariana Duarte Silva, director of Village Underground (VU) and the brains behind Skoola

Music – and learning it as a group – is also an awakening for creativity and critical thinking, imagining other worlds, approaching people, increasing self-esteem and a sense of belonging. That’s why our way of teaching music – the more urban and contemporary side that young people hear – is structured into three axes: music production, creation/ composition, and performance, via a curriculum design that unites the basic principles of musical instruments with new possibilities for making music using technology. This has created a community where everyone contributes to each person’s development.

Skoola is an academy open to young people from all social backgrounds. We have people from neighbourhoods such as Chelas, Quinta do Loureiro and Liberdade, others who live in Santa Casa da Misericórdia homes, others with cognitive issues from state schools (none of whom pay, they all have scholarships), and boys and girls from families whose financial situation enables them to pay to attend Skoola. There is a symbiosis between them all when making music, as well as during breaktime: they play basketball, dance, draw and chat, and have their WhatsApp groups. Amongst the many stories that have revealed talents, friendships, artists and other possible futures, is the one of Ricardo, a 14-year-old from Guinea-Bissau living in Portugal on a health visa for treatment of a problem in his eye, which is making him blind. He came to Skoola with his face covered by his hoodie, not saying anything, but once he discovered he could play the piano, sing, write lyrics and learn how to get up on a stage and mix like a DJ, he ended up wanting to participate in not just the lesson for his age group, but all the other sessions, too. These days, Ricardo calls up Pedro Coquenão and Karlon Krioulo (project staff members) and goes to make music with them in our studio.

My answer to the previous questions has answered this one, too. We’ve spoken to headteachers, psychologists and social workers from state schools, whose young people have attended Skoola, all of whom spoke of the urgent need to implement this kind of project in schools regularly and constructively. Marquesa de Alorna school, for example, having witnessed three of their students attending our summer course, has already asked us to quote for weekly Skoola lessons during the coming academic year.

Interdependence vs Independence

MAT DRYHURST, musician, multimedia artist and one of the most challenging thinkers in the music industry, has no doubt that the musical ecosystem as we know it is being “eroded year by year” and “replaced by ahistorical and algorithmic platforms.” There’s no going back, he says, but there’s a need to enact counter-narratives and other ways of doing things to make this ecosystem more sustainable and ethical, equitable and inventive in light of new circumstances.

“People just need to do something, like literally anything… be less risk-averse”, he states. “Independent music – whatever that means now – is like a totally comfortable, well-worn template”. A domesticated, distorted ideal with serious implications for the creative economy, for artists’ working conditions, and the creation of truly strong communities.

“The problem with fetishizing independence, as we see with the platform economy, is that when you strip away those support mechanisms, through cost-cutting, ultimately you end up with pretty hollow results”, he muses. “The dream of independent music was this myth of absolute sovereignty, “nobody can tell me what to do man”. In many ways, independence has led to isolation. Feeling like no-one has your back. Feeling like you have to make safe choices. Feeling in competition with everyone and making choices based upon that impulse, which is not the healthiest mindset to make great art or challenge anything”.

That’s why Mat Dryhurst has become a staunch defender and advocate of the concept of interdependence, promoting the possibilities of a new decentralised creative economy (check out the podcast Interdependence, which he runs with artist and composer Holly Herndon). “Everything special and ambitious ultimately takes a large group of people, who need to be respected and compensated to make the whole operation work”, he tells us, referring to the cooperative logic behind projects such as the community streaming platform he’s involved in, Resonate (it’s worth following other initiatives like herstoryDAO, Friends with Benefits or Mycelia).

“I think that interdependence represents the reassertion of value and values into culture by constructing new institutions and protocols”, he points out. “People are already doing it in some corners. I’m personally quite a fan of UK grime and drill music, and even within the challenging conditions of YouTube I am impressed to see how different artists, producers, influencers are basically all colluding to amplify what each other is doing”.

Dryhurst says he’s particularly interested in new tools that can be employed to make this type of cultural movements, and musical networks, “more financially independent”. But how do we achieve this, with big corporations always on the lookout for ways to capitalise on these subcultures? The artist and researcher suggests that Web3 might have the answers. “Cultures embrace capitalisation ultimately because they need access to capital, and Web2 has done a bad job of providing that. Which is why over the past decade it has become understandably normalised for artists to team up with brands, because most people do not pay for culture directly anymore and artists need to eat”.

“There are many different approaches you can take with Web3 tools, but one of the proposals that I find compelling is the opportunity to offer a community ownership in projects”, he adds – and that’s something he and Holly Herndon are trying out via Holly+, based on shared stewardship known as DAO – Decentralised Autonomous Organization. In spite of his enthusiasm, Mat Dryhurst admits that Web3 is not immune to monopolies, nor is it “some kind of horizontal and equal utopia”, nor will it bring an end to capitalism. That said, he argues that it contains “more tools to prevent such monopolisation from happening across the board” and permanently. And that “it’ll be better”.

“I think one of the core things we need to embrace to make those things better is to break up the centralisation of any one art or music market. Music is heavily concentrated on streaming platforms now. My hope with Web3 is that we see thousands of distinct mini economies that serve the communities”. That’s also why, he highlights, we need more instruction concerning Web3, which is still pretty baffling for most people – and also so that artists can understand how to make the most of these new tools.

/ Translation by Naomi Teles Fazendeiro